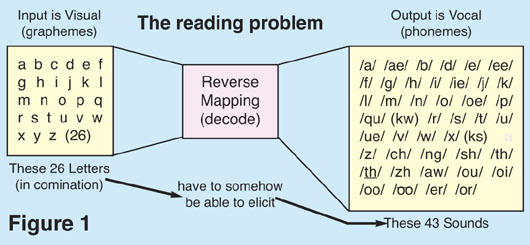

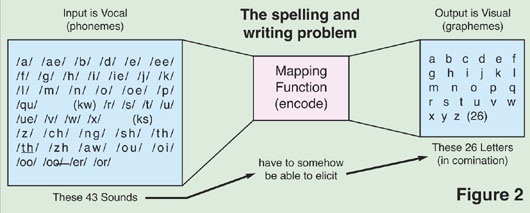

The first problem with reading is that in English there are 26 letters (graphemes) in the Roman alphabet and there are 43 sounds (phonemes) in our spoken language. Now, it doesn't require a rocket scientist to see that some of the letters will have to represent more than one sound.

The first problem with reading is that in English there are 26 letters (graphemes) in the Roman alphabet and there are 43 sounds (phonemes) in our spoken language. Now, it doesn't require a rocket scientist to see that some of the letters will have to represent more than one sound.

Soft c, which can be pronounced as /s/ or /k/, and soft g, which can be pronounced as /j/ or /g/, are examples among the consonants. Other examples include groups of letters that represent a single sound. Th, wh, ch, and sh are examples of this pairing method of stretching the 26-letter set to fit the set of 43 phonemes.

But vowels are the real headache: they are chameleons. Each of the vowels has several alternative pronunciations. I'm not going to try to list those here. There are other examples of the problem of mapping letters to sounds.

Paul Hanna, using - the then new - computer technology, worked on that back in the mid-sixties and came up with a very large number of rules.

As a result of Hanna's research, educators became much more sensitive to, and knowledgeable about, phoneme-grapheme correspondences.

As I'm writing this, the television is on and it is tuned to Channel 6, our Public Television Station here in Denver. A fellow is talking about learning how to play the piano. It strikes me that the piano is an excellent illustration of the problem with reading. Every key on the piano makes the same sound every time it is struck. And if one wants that sound, he hits one and only one key. One key, one sound: no mapping problem. Fantastic! wouldn't it be great if reading and writing worked that way?

But it doesn't work that way, so we have to try to figure a way to teach it without teaching an impossibly large set of rules for reading and spelling.

A sort of rough "standardized" sequence of presenting the letter/sound combinations has evolved. It's based on the idea that we should teach the simple concepts first, then proceed to the more complex ones. Here's what one sequence might look like: Simple consonants c, b, t, f, s, m, n, g, d, h, l, j, k, v, p, w, y, z (in any sequence) combined with the short vowel sounds /a/ /e/ /i/ /o/ /u/. Using these consonants and short vowel sounds allows a large number of three-letter words to be formed. Try it and you'll see what I mean.

Use some old business cards (everyone has a bunch of 'em) print those twenty consonants and the five vowels on them and then, using combinations of them three at a time, see how many real words you can form. Those words make up a good set of words to teach the emerging young reader.

These beginning words aren't enough to make sentences though, so we have to add some other words. We call these other words - ones that don't fit the simple rules, and simply must be memorized - sight words. [See Mary Pecci's article in PHS #76, "Free Your Children from the Sight Word Trap," to discover how to vastly cut down on this amount of memorization. - ED] Some sight words such as I, was, one, two, etc., if added to a set of flash cards made up of the simple three-letter words mentioned above, will make a simple vocabulary that can make real reading material, i.e. sentences and paragraphs, for a beginner.

So, here's what a parent can do to begin the learning of the code:

- Let the child watch and help as you make the letter cards. Pick up a blank card. Say the sound /c/. Write the letter on the card c. Get another blank card. Say the sound of /a/. Write the letter a on the card. Get a third blank card. Say the sound of /t/. Write the letter t on the card.

- Lay the cards out so they are side by side spelling cat. Slide your finger over the letters left-to-right and say - slowly - "cat."

- Get another blank card. Write the word cat on it.

- Get another blank card. Say the sound /b/ as you write the letter b on it. Do this for some other consonants, for example f, m, and s.

- Make another short vowel card. Let the learner hear you say the sound of /i/ and watch while you write the letter i.

- Using the collection of letter cards you have, you can assemble words such as cat, fat, mat, bat, and sat with the /a/ card. As you assemble, slide over, and pronounce these words, and make a word card as described in step 3, make sure the words are right-side up to the learner. You may have to do them upside down to yourself. Adding the /i/ card, you can make (and sound out) sit, fit, bit, Tim, fib, and mitt.

- Work with the child regularly. Don't rush. Use lots of repetition. Add just one or two letters at a time. Add only one vowel until you have all of the short vowels (/a/ /e/ / i/ /o/ /u/ to work with. If the child's attention seems to wander, stop.

That's enough for now. You can keep busy making letter cards and word cards with your young learner for several months with just this much.